Soft thinking is a like a contagious disease. If you don’t treat it early, it will spread to the masses and become endemic.

Almost every day, I ask myself if I am guilty of soft thinking. Have I underestimated complexity? Have I accepted weak evidence?

Here is the problem: thinking about the quality of your thinking produces tension. One force is that getting by in medicine requires pragmatism. You must, to some extent, go with the flow. The opposing force is that the high prevalence of soft thinking makes critical thinking stand out. You can look like a nihilist, an outsider, even a nut-job. Some will even question your motives.

At the recent American College of Cardiology meeting, we learned the results of a small Canadian study of eliminating copayments for beneficial cardiac medicines in older adults with low income.

The results of the ACCESS trial force us to think about established beliefs regarding preventive healthcare.

Let’s set out two commonly held ideas, which I will revisit in the 'teaching points’ section:

One is that preventive healthcare produces health. For instance, trials have shown that numerous cardiac medications reduce the future rate of bad outcomes. Statins, for instance.

The other accepted idea is that reducing barriers to getting people on these meds would not only improve outcomes for all but also decrease disparities in health outcomes.

These were the hypotheses tested in ACCESS. Canadian investigators randomized nearly 5000 older adults with high cardiovascular risk and low income to receive free high-value medications or standard Canadian care.

Those on the active arm had their copayments eliminated for 15 types of medications that had trial-level evidence of reduced outcomes. Statins, other cholesterol-lowering agents, beta-blockers, ACE-inhibitors, etc. The control arm had to pay the typical 30% co-payment.

The primary outcome was a composite of death, heart attack (MI), stroke, coronary revascularization, or hospitalization due to heart disease.

Results:

The average cost reduction from the waiver of copayments was about $1100 per person or $35 per month over the 35 months of the trial.

The rate of the primary outcome was not significantly reduced in the group that had no copayments. 521 vs 533 events.

None of the components of the primary outcome varied. Nor did changes in QOL or health care costs.

Statin adherence hardly budged (0.72 vs 0.68). There was no difference in ACE-ARB adherence.

Teaching Points

These are remarkable findings.

First consider the study subjects. The authors enrolled people most likely to benefit. These were older patients (74 years old) who had low income and high cardiac risk.

Now consider the intervention. All of these medications have trial-level evidence of benefit. They should cause benefit. Also, free medications should improve adherence. Low-income seniors will surely be sensitive to cost.

A perfect scenario for success. Yet there was no difference in outcomes. A decade ago, I would have been surprised. Not anymore.

I have come to understand that—on average—it is hard to show that preventive healthcare produces better health.

Here I cite evidence. The RAND and Oregon health insurance experiments and the Karnataka India experiment have found that more preventive care did not significantly improve outcomes.

A recent JAMA paper comparing Medicaid expansion vs non-expansion states found that “working-age adults with low income in Medicaid non-expansion states experienced higher uninsurance rates and worse access to care than did those in expansion states; however, cardiovascular risk factor management was similar.”

The MI-FREE trial found that giving free medications to patients after heart attack did not improve outcomes. Same with the ARTEMIS trial, which reported that vouchers for the vitally important post-stent medicine, clopidogrel, led to no difference in major adverse cardiac outcomes after heart attack.

The ACCESS trial shows exactly the same thing.

The Challenge of Preventive Healthcare

Prevention of disease is far more complex than simply adhering to guideline-favored medication.

Now you have to be comfortable with competing thoughts in your brain. One thought: the trials are real. In a controlled setting, with selected patients, and proper randomization, preventive medications cause lower event rates.

But consider three competing thoughts:

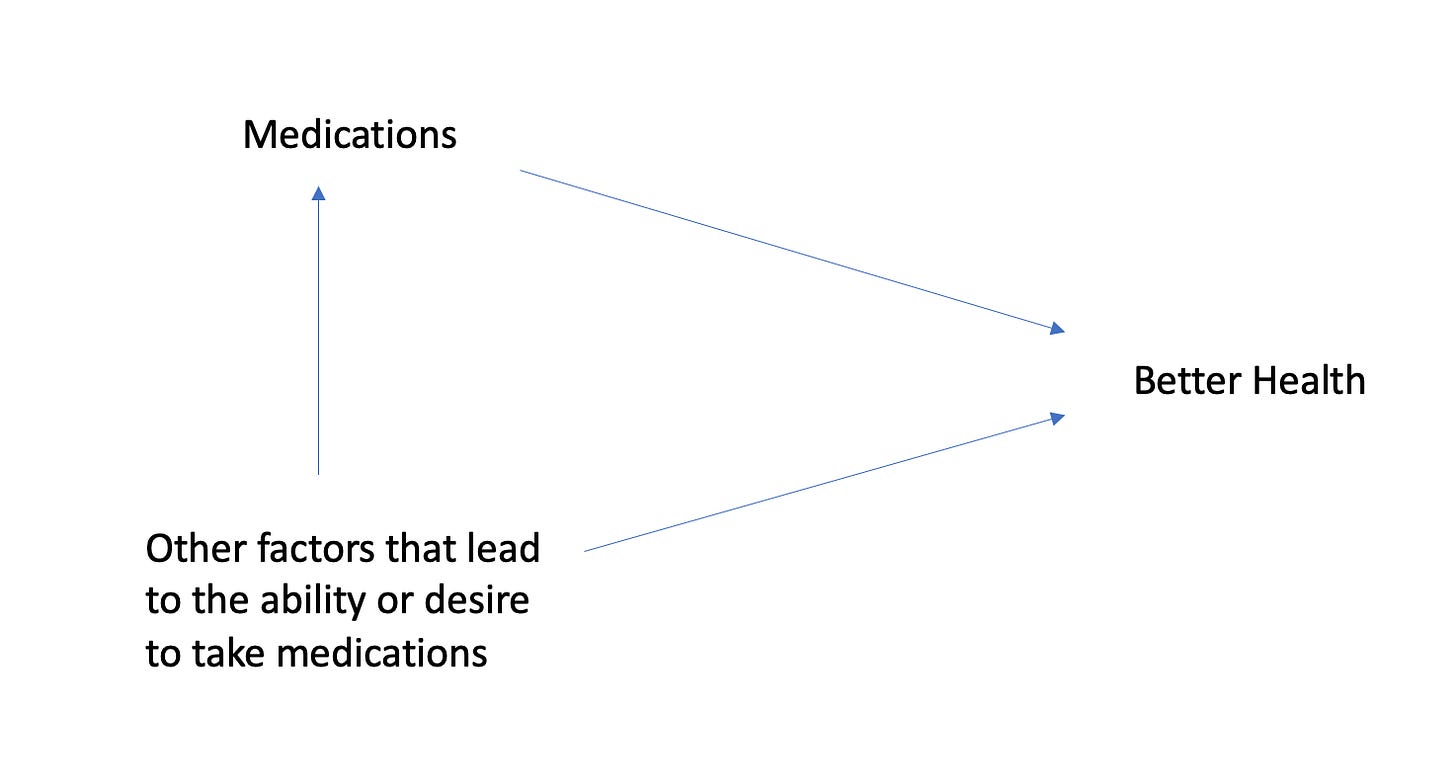

In real-world practice, the ability to adhere to medications is likely a strong marker for a healthier patient and it those other factors that lead to better outcomes. For instance, I know that the big four heart failure drugs work, but I also think the ability to take four drugs selects patients destined to do better.

Trials do show that our anointed preventive therapies produce statistically robust benefits. But in absolute terms, the reduction in future risk is modest. Statins, for instance, reduce the relative risk of future events by 25% but this translates to a 1-2% absolute risk reduction for future cardiac events. That is not nothing, but the average 75-year-old-not-selected-to-be-in-a-trial faces many competing risks of death. Not just a non-fatal MI or stroke.

Third, and this is MOST important: Health turns mostly on luck. The luck to avoid freak events (brain tumor, pancreatic cancer, car wreck, ALS etc); the luck to live in a supportive family; the luck to live in a nice community, one with sidewalks and parks, and the luck to have parents who had good health.

Finally

Do not mistake any of this for nihilism.

I strongly believe doctors help people. We help most when people present with illness. But we also help prevent future illness, not only with pills, but advice about exercise, diet, and not smoking.

My point in writing this essay is to emphasize that the danger of soft thinking is hubris. Health and healthcare are complex.

There are many factors besides adherence to medication on the causal pathway to good health. Everyone should be ok with that.

Excellent, thought provoking essay!

A common challenge for all professionals is to make decisions or judgments in an individual situation using averages. Conclusions based on averages don’t really apply to individual situations. There is a large amount of uncertainty.

So our job as a professional, especially when managing risk, is to understand the nature of uncertainty, key drivers and impact of potential intervention or no intervention.

That is how we earn out paychecks!!

Thought provoking article once again. As you say, in controlled environments in the context of a clinical trial, we know these drug classes work (in isolation). We also know, per Salim Yusuf’s work I believe, as well as Secure study from ESC 2022, that polypill with several classes of agents is effective.

As you say, I don’t think this study negates those findings. However, it does raise questions about the translation of those RCT findings to the real world (which is and should always be a consideration). When you take these meds, they work; but they can’t work unless you take them. And there are myriad reasons why people don’t take them.

In this case, however, I would question the external validity of this study. The cost differential was only $35 a month. I don’t mean to make light of this for low/fixed income seniors (and I live in BC which is next to Alberta, and our drug coverage is similar), but it doesn’t necessarily apply to scenarios where the cost differential may be more substantial. Also, the PDC80 (their surrogate for scripts filled, and by extension, presumably pills taken) showed only 3-4% difference in both RASS blockers and statins. This difference was statistically significantly different, but I don’t know if that is a clinically meaningful difference.

So instead, I would interpret this study as showing that, when the medication Copay cost is not huge, and getting meds for free does not make a huge financial difference, it does not result in a huge or clinically significant difference in medication compliance. That small absolute difference in compliance does not translate into clinical outcome endpoint differences. Whether such a policy would make a difference when dealing with more expensive therapies, or where the financial burden is substantially higher in general, remains unknown.