Older cardiology trials were often hugely positive. Newer cardiology trials not so much

I have a theory why this is but a colleague suggested an alternative reason

I wrote yesterday over at Sensible Medicine about the RALES (circa 1999) trial of spironolactone vs placebo in patients with heart failure. Patients treated in the spironolactone arm had an 11% lower rate of death. The number needed to save a life with this daily inexpensive pill was a mere 9—a massive effect size.

The thing about the 1990s era of cardiology is that there were lots of hugely positive trials similar to RALES. The ACE-I, beta-blocker and ICD trials in heart failure also found massive reductions in death. Other examples include the aspirin and revascularization trials in acute MI. (Please check out our Cardiology Trials Substack where we attempt to chronicle all the major trials in cardiology.)

In that era, things that worked in cardiology did not result in a small reductions in composite endpoints; they lowered death rates. Modern cardiology now celebrates wins with statistical significance in composite endpoints—often driven by the soft components of those composites.

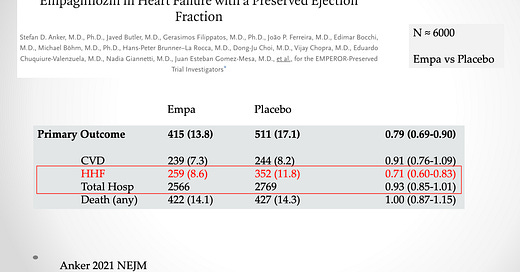

Consider heart failure hospitalization. It sounds like a reasonable endpoint—a good thing to prevent. The problem is that in some trials, hospitalization for heart failure represents only a small fraction of total hospitalizations.

This slide shows an example. From the EMPEROR-PRESERVED trial of empagliflozin vs placebo. Yes, hospitalizations for heart failure are 29% lower with the drug. But. But. This endpoint represents only 10% of total hospitalizations.

The puzzle: older trials found big gains in major outcomes (death) and newer trials struggle to show incremental gains in composite endpoints, such as one of many causes of hospitalization.

My working answer: In the heyday of cardiology, we made big gains because there were big gains to be had. This slide shows the issue. The first three trials were older trials. The control arm had higher death rates than the newer trials.

The simple answer to the puzzle is that it’s hard to improve on so many great therapies. In the PARAGON-HF trial, for instance, only 3% of the control arm died per year. That’s pretty low; how do you lower it further?

I see this in my ICD clinic. Before we had heart failure drugs, patients with heart failure would die because their heart just wore out. Now, patients with heart failure who take the 4 classes of drugs don’t suffer deterioration of heart function. They live long enough to die of non-cardiac causes. It would be hard for a new cardiac drug to improve further on this extension of longevity.

A New Theory — Trial Pre-registration

On my private messaging group yesterday, an academic cardiologist suggested another reason that older trials often had huge gains relative to newer trials—that is, pre-registration of trials.

In 2005, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) initiated a policy requiring investigators to deposit information about trial design into an accepted clinical trials registry before the onset of patient enrollment.

I, and maybe you, forgot about the trial pre-registration rule—probably because it is so normal now. For instance, before I write my review of a big meeting’s late-breaking trials, I go to clinicaltrials.gov to see what the investigators planned for their trial.

Pre-registration was felt important because it forces investigators to have a plan—including things like choice of endpoint, duration of trial and statistical approach before the trial. Publicly declaring your experimental plan prevented (mostly) reporting the best results and downplaying the less impressive endpoints.

Let’s say you planned a trial of a new cardiology drug. You declared your endpoint as death from cardiac causes. Then, when the trial results came in, CV death was not different, but overall death was lower. If the trial was not pre-registered, there might be a temptation to focus on the overall death rather than the primary endpoint.

We reviewed the CAPRICORN trial and found some curious changes of endpoints and conclusions. Circa 2001.

My Conclusion to the Puzzle

Indeed there is a strong temporal correlation between pre-registration rule and the onset of less-positive trials.

I am not sure it is causal. I still lean more heavily on the explanation that newer trials are harder to win big on because we have had so many discoveries.

But the pre-registration idea made me Stop and Think. JMM

You made some good points but let's stop and think about the composite outcome components issue. An overriding principle in my mind is to construct endpoints that reflect how patients feel or fare. Hospitalization is bad and should be counted but not as much as say MI or stroke. If you feel that non-HF hospitalization is bad but is not as bad as HF hospitalization then in an ordinal outcome rank non-HF hosp as less severe than HF hosp (and this less severe than MI and MI less severe than death). The end result of this is that we will be able to get a single expression of which treatment provides better patient outcomes, and will greatly reduce sample size requirements. More at https://hbiostat.org/endpoint

I can see how requiring the preregistration of the endpoints would dramatically reduce positive results.

Suppose we do a large RCT testing whether eating jellybeans causes cancer. The results are negative. But the lead scientist is convinced jellybeans cause cancer because he has seen it so many times in his practice. It occurs to him, maybe it’s a particular flavor that causes cancer. There are 20 flavors of jellybeans, so he looks carefully at the data. Sure enough, the green ones appear to cause cancer as the p value is under 5%.

Of course, with 20 flavors at least one of them is likely to show a false positive. Preregistering endpoints puts an end to this kind of nonsense. To clear this up maybe someone should try to replicate a few of those old studies.