Medical Decisions: Some are Easy and Some Not So Much

Perhaps you’ve noticed that medical decision-making is in the news these days. Here is a short post about the basics. I hope you find it relevant.

Let’s start with the easy decisions: sick patients who are asking for our help.

When someone falls and breaks a hip, the decision is easy. You fix it. When someone presents in shock because of AV block and a low heart rate, you place a pacemaker. When someone presents with bacterial infection, you use antibiotics.

It gets trickier when we consider preventive interventions.

Here, the patient—or, we might say ‘person’ rather than patient--is free of complaints. Nothing bad has happened. Something bad might happen in the future. Our intervention aims to reduce the odds of that bad outcome.

The benefit of preventive therapy, therefore, can only be considered as a reduced probability of that outcome.

Statin drugs, for instance, reduce the odds of a future heart attack. Anticoagulant drugs given to patients with atrial fibrillation reduce the odds of a future stroke. Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) reduce the odds of dying.

But…But.

There are two big snags with preventive therapy.

One is that all medical interventions come with the potential for harm. Statin drugs can cause muscle toxicity, anticoagulant drugs increase bleeding and defibrillators can cause a host of problems.

The other snag with preventive therapies are the modest effect sizes.

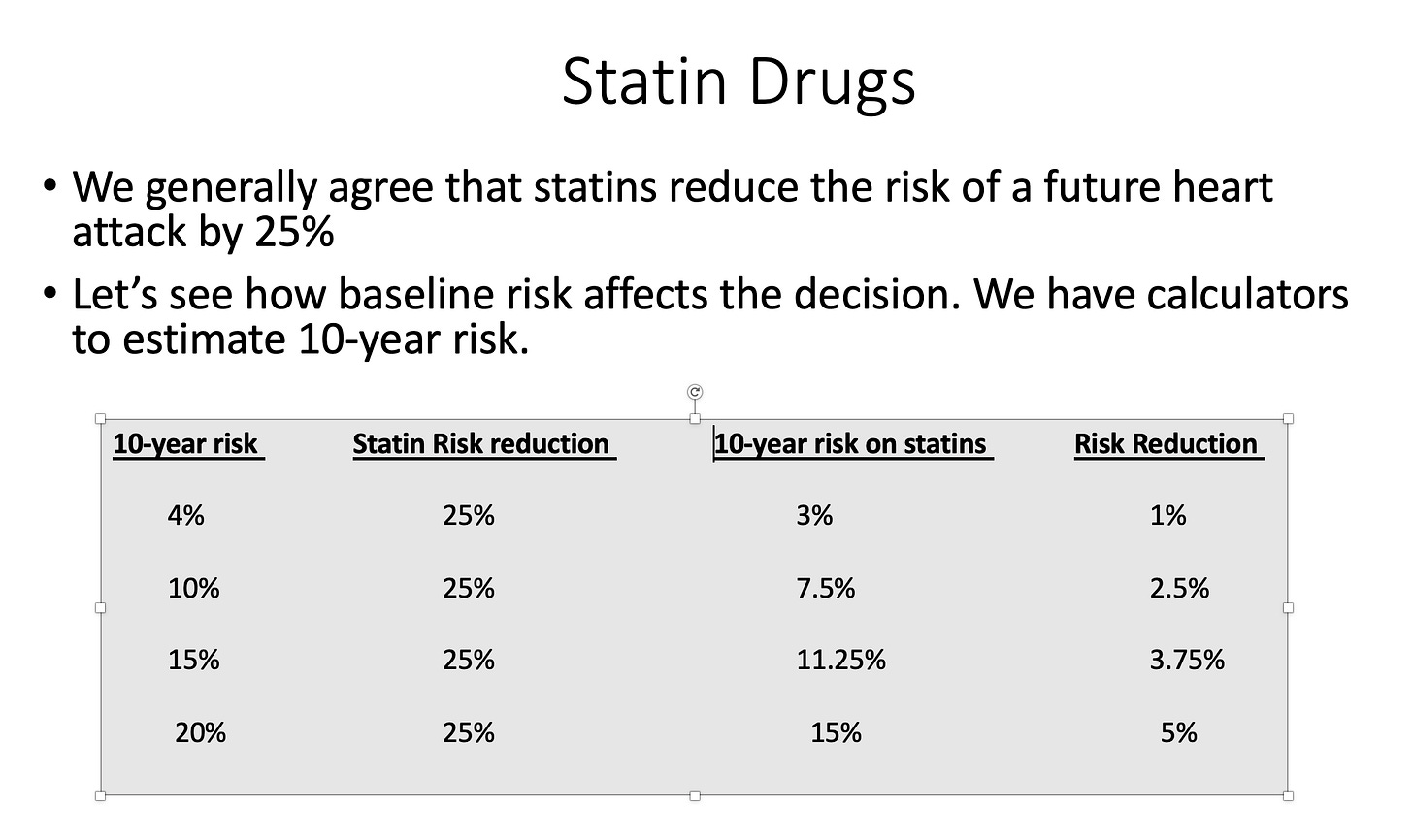

Statin drugs reduce the risk of a heart attack by about 25%. If your 10-year risk of a heart attack is 4%, then your risk on statins is now 3%.

That is not a big difference. When effect sizes are small, it’s fair to say that most people who take a preventive therapy get neither benefit nor harm.

So, you ask…

How do clinicians decide when to recommend a preventive therapy?

For instance, you could say, rightly, that the vast majority of sudden cardiac death occurs in patients without heart failure; therefore, why not implant ICDs in any patient with any amount of heart disease? And since we know statins reduce cardiac risk, why not put them in the water? Same for anticoagulants in AF; if we anticoagulated all patients with AF, we would prevent lots of strokes.

You probably recognize these ideas as foolish, but it’s instructive to consider why, exactly, they are foolish.

Clinicians decide to use preventive therapies by a process called risk stratification—which is awful jargon but quite simple in theory.

We estimate a person’s baseline risk of having a bad outcome in the future and then decide if the potential benefit from our intervention is worth a) the costs, b) the burden of taking a pill every day or having a procedure, and c) do the odds of benefit outweigh the odds of harm?

Let us first focus on the balance of benefits and harms. The reason we don’t recommend defibrillators in patients without heart failure is that the absolute risk of sudden death in each person is so low that the harms of the ICD outweigh the potential benefits. For instance, if we put ICDs in 1000 low-risk patients, the device might save one life, but cause 50 serious adverse effects.

Same with anticoagulants. If we used these tablets in low-stroke-risk patients the higher rates of bleeding would be greater than the lower rate of strokes.

It’s all about the balance of probabilities—benefit vs harm.

Even if a preventive measure has a very low risk of adverse effects, if it is used in people with a very low-risk of bad outcomes, the harm can be greater than the benefit. (Consider re-reading that sentence.)

In general, the higher the baseline risk, the more likely it is that the preventive therapy will deliver a net benefit. Look at the figure: as the 10-year risk of a heart attack goes up, say, because of age or smoking or diabetes, the greater the benefit of the statin.

(There are exceptions to this baseline-risk rule—especially for older patients with many problems. But that is for another post.)

Costs also figure in the decision. Again, even if the preventive therapy is not that costly (statins and anticoagulants come in generic forms), if you treat oodles of low-risk people, costs accumulate. And money spent on ineffective low-value things means less money is available for important things.

Risk stratification is an imperfect exercise. The exact threshold of when risk is high enough to warrant taking preventive action varies. Professional societies often disagree on these thresholds.

As such it requires input from the patient (or person). I call these preference-sensitive decisions—and it delves deep into behavioral psychology and it requires a shared understanding of medicine.

Take heart disease; a person may want to do everything possible to reduce the risk of a bad outcome and this person will choose to take the statin. Others see the risk reduction as small and not worth the trouble of taking a pill every day. They see the fact that most people get neither benefit nor harm. The job of clinician is to help patients make the best decision for them—not us.

In summary, medicine is most pure when we fix problems that bother people. There are no probability concerns in fixing a broken hip because there is a 100% chance that that person will not walk without a repair.

Prevention is surely important but is a zillion times more nuanced.

You have to consider together the baseline risk, the degree of benefit and harm of the intervention, its costs, and how a person feels about these factors.

And.

Deep within these considerations lies a core philosophy of how much we think we control future outcomes.

As I’ve grown older and practiced longer, I have become increasingly skeptical that we control nearly as much as we think we do. And for that I am grateful.

Absolutely one of your best, Dr. Mandrola, and the clearest explanation I've come across of how risks & benefits are not easy to evaluate in preventive medicine, and why it's important for patients to do their share of the work and think things through. Many thanks.

I enjoyed reading this post and I liked your comment that our ability to control future events is less than we think we are capable of. While I certainly do not want my patients to be blissful because of ignorance, I worry about creating anxiety in them by trying to prevent everything that can go wrong with them in the future.