If only critical appraisal was this good for *all* studies

JAMA published a study showing major benefits of a pill given to patients after heart attack. Instead of celebration it has received serious criticism. Why?

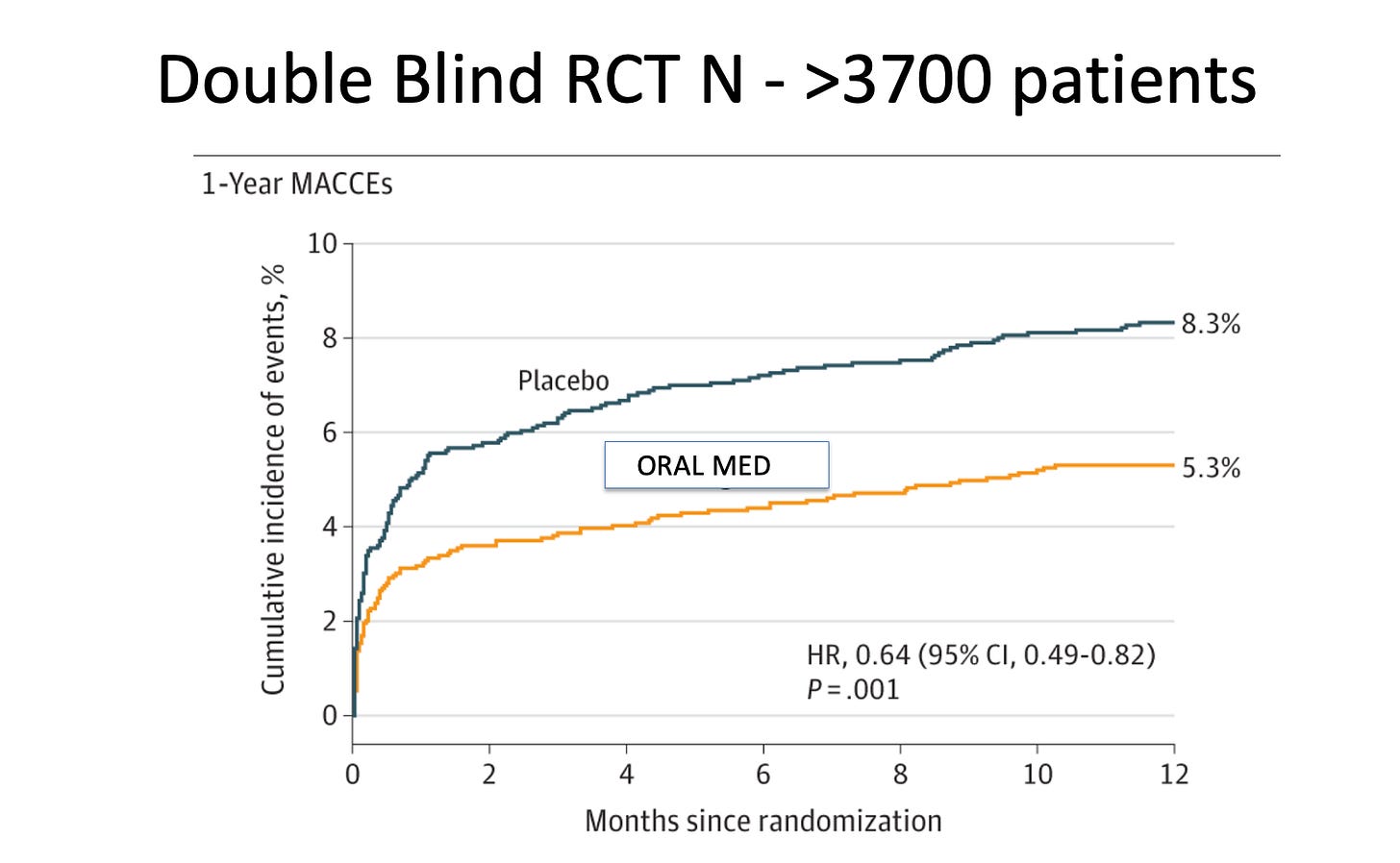

Let’s start with a picture:

This is the Kaplan-Meier curve, from an RCT, published in JAMA, of an oral medication vs a placebo given to patients after a myocardial infarction (MI).

The group on the drug sustained a 36% reduction in the occurrence a major adverse cardiac or brain event vs placebo. Outcomes included cardiac death, MI, emergency coronary revascularization or stroke.

The trial enrolled more than 3700 patients and the absolute risk reduction was 1.8%. The number needed to treat to prevent one bad event is 55. (For comparison, the NNT of alirocumab, an FDA-approved drug also used after MI, has an NNT of 62.)

The risk of death from any cause at one year with our mystery drug was 5.1% vs 6.6% in the placebo arm. This 23% reduction had 95% confidence intervals ranging from 0.59 to 1.01 (nearly significant).

There were no substantial adverse effects from the drug.

The authors of the CTS-AMI trial pre-registered their study on clinicaltrials.gov and published a full trial rationale and protocol. They designed the placebo to match the normal drug, had a blinded clinical trial adjudication committee, and they had low drop-out rates. In other words: trial conduct seemed pretty good.

You’ve probably never heard of this trial or this compound. Likely because the oral medication is Tongxinluo—a traditional Chinese medicine used previously to treat angina. It has been approved in China since 1996. And it is not one thing. It is a mixture of things made from plant and insect parts. Insect parts.

The authors cite in their introduction more than a dozen studies suggesting why and how the drug may have cardioprotective effects.

The Response

The CTS-AMI trial reported statistically robust and clinically relevant benefits. That is what we want in cardiology.

Yet, there was no celebratory editorial. Instead the accompanying editorial was suspicious. After describing the positive results, the editorialist began the next sentence with the phrase, “At first look the data seem to support…”

In the next paragraphs and 640 words, Dr. Richard Bach offered criticisms of the study. Appropriate things, such as, what is in the drug, how does the trial generalize to other populations, differences in patient populations and peculiarities of outcome events.

But that wasn’t the only criticism the positive trial received.

Dr. Gregory Curfman, the executive editor of JAMA, wrote an “editor’s note” in which he explained the tension in deciding to publish this study.

In making a judgment about the validity of this research, the editors were faced with the task of walking a fine line between skepticism and plausibility. The authors claim that Tongxinluo may promote coronary microvascular perfusion, but they have not identified a specific component that would cause this action.

I read a lot of medical studies, and the combination of a doubting editorial and an anxious editor’s note for a positive study is highly unusual.

My Thoughts

The reason that stalwarts of the medical establishment struggle with this trial should be obvious. The trial was conducted in China. It involved a compound containing many things, including insect parts.

US doctors have never heard of it. We can’t explain how it works. It’s mysterious. Yet a response to the unknown-mechanism worry, is that no one (really) understands how SGLT2 inhibitors confer renal and cardiac protection. Yet, we use SGLT2i because of trial results—like CTS-AMI.

Another explanation I heard on social channels employed Bayesian reasoning. Yes, John, it was positive data, but if its probability density function was combined with the PDF of super-pessimistic priors, our posterior results are not as convincing. My question to this group is how, exactly, do you know anything about the drug’s priors? And. When I began cardiology, bayesian priors got crushed when it came to antiarrhythmic drugs after MI and hormone replacement therapy in post-menopausal women.

So we doubt CTS-AMI. We want replication. Verification.

Which is good. But perhaps there is selective or outsized skepticism here?

Two Examples Where We Accepted One Trial

We should always want these things for new therapies. Yet mainstream medicine seems to suspend our skepticism for some things.

Exhibit A: Sacubitril/Valsartan. This drug, known as entresto, gained FDA approval and favored status after only one positive trial, called PARADIGM HF. I have wondered about this drug. Subsequent trials have not replicated its benefit. Yet it is widely accepted in US practice.

Exhibit B: Transcatheter edge-to-edge repair of the mitral valve for secondary MR. One trial showed that the invasive procedure did not work. Another trial showed that it was nearly as good as clean drinking water.

Which is it? We accept one trial and reject the other.

Proponents argue that the patients were different. Maybe so; but the Table 1’s in the two trials don’t appear that different to me.

Conclusion:

My point is not to persuade you that Tongxinluo is a wonder drug. I am skeptical. We need more data.

The point here is to highlight selective skepticism. Everyone is fine to apply the principles of proper scientific skepticism to an unknown medicine from a faraway country and a different culture.

Yet mainstream medicine is replete with examples where we exuberantly accept therapies with single trials—as in the cases above. And don’t get me started on some others. The list is long.

What I propose is that we apply Tongxinluo-level skepticism to all our shiny new therapies. If you want replication and verification of Tongxinluo, you should want it for the next new thing.

What do you think?

I’ve often pondered why we accept as standard of care drugs or therapeutics that have single digit absolute risk benefit? That means 90% of patients get no benefit?? Most blockbuster drugs fall into this category

Follow the money! Drug companies will not have huge profits.