Expertise is Over-Rated

Understanding truly beneficial medical treatments does not require content expertise

You have surely heard the phrase, “stay in your lane.” Cardiologists should stick to cardiology, oncologists to cancer and so on.

When it comes to evaluating evidence, this is flawed thinking.

I will not argue that expertise is worthless, clearly it is not, but let me show you the problem with what we in medicine call “content expertise.”

Exhibit A — Strong Unbiased Evidence

Let’s say your Mom has congestive heart failure due to a weak heart muscle and the doctor has prescribed a drug called carvedilol—a beta-blocker.

You look up beta-blockers and learn that these drugs can actually reduce the strength of the heart contraction. That is a puzzle. Why would the doctor think this is a good thing?

This is where evidence comes in. Now you search: “carvedilol and heart failure trial.”

You come to a randomized placebo controlled trial of more than 1000 patients with heart failure and a weak heart muscle.

In the group that received the sugar pill, 8% of patients died; in the group that received carvedilol, 3% died. You read that the p-value was less than 0.001. You Google that and learn that if carvedilol had no effect on death rate, the chance of getting this data (or something more extreme) was nearly zero. IOW: it was not a fluke.

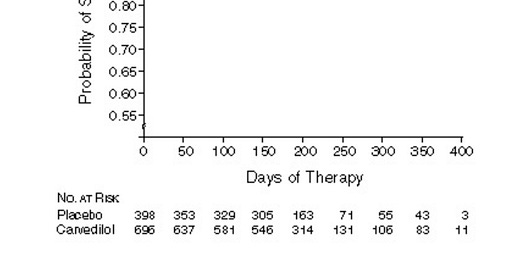

This image shows what a 65% reduction in death looks like over time. Anyone can see the benefit.

This evidence was so strong that the trial was stopped early because it was unethical to keep giving placebo to patients.

You could (and should) Google more about beta-blockers in heart failure. You would learn that multiple trials of multiple different kinds of these drugs have shown similar benefits. This is called replication—and it is a good thing.

I tell you this story because if a Martian came down to Earth with no knowledge, she would be able to see that carvedilol is generally a good thing to give patients with this condition.

Exhibit B — The Bias of Experts

An expert easily gets attached to what they do. This is rarely nefarious; it is simply human nature to think that what we do helps people.

Take opening blockages in the coronary arteries. Heart attack due to an acutely closed artery is a leading cause of death so it follows that opening these blockages before hand would reduce heart attacks and death.

In 1997, just before the dawn of the current era of coronary stents, experts published a study (in the prominent journal, The Lancet) on using plain old balloon angioplasty—a once common technique used to open serious blockages.

The Rita-2 trial randomized about 1000 patients to either angioplasty or medicines. The experts chose to measure two important primary outcomes—death and heart attack. They also measured other things as well, such as relief of chest pain.

In the group that had their artery opened, 6.3% of patients had a primary outcome (death or heart attack).

In the group that had medical therapy, 3.0% of the patients had a primary outcome (death or heart attack).

This image shows what a doubling of the risk of death or heart attack looks like.

The Martian that I introduced before would look at this data and conclude, gosh, it sure looks like medical therapy was the better one.

That, however, was not the conclusion of the expert angioplasty doctors who did the experiment.

I will quote exactly what they wrote:

In patients with coronary artery disease considered suitable for either PTCA or medical care, early intervention with PTCA was associated with greater symptomatic improvement, especially in patients with more severe angina. When managing individuals with angina, clinicians must balance these benefits against the small excess hazard associated with PTCA due to procedure-related complications.

You can see that they mostly ignored the primary result of the experiment, and focused on an endpoint (relief of chest pain) that turned out better. They called the doubling of risk of death or heart attack a “small excess hazard.”

This, by the way, is called spin. I’ve been part of a study that shows how often it is present in the cardiac literature. Teaser: very often.

The neutral observer of Rita-2 would have also surmised that these extreme results would have a) reduced the number of angioplasty procedures and b) caused experts to reconsider the larger idea that stable blockages needed to be opened.

History shows that nothing of the sort happened. The decade that followed 1997 saw major increases in these procedures.

Herein lies a major problem with content expertise—conflict of interest.

Many people focus on financial COI, but I will argue in future writings that it is far more complex than that.

Humans do science; and human scientists will have prior beliefs and biases that influence how they design, conduct and interpret the experiments that guide medical practice.

Neutral observes don’t have these biases.

I have obviously chosen two extreme examples on the benefit of being a neutral observer of medical science. There are many more.

John, these are crystal clear concepts, but they crash against professional interest of performer physicians!!!

Thank you for relinking this on Twitter. I missed it the first time. I agree completely.