A New Proposal for AF studies: Jettison the "Blanking Period"

Since the beginning of AF ablation 20 years ago, studies have used a 90-day blanking period after the procedure where AF episodes do not count. It is not right.

I presented Friday at the Western AF symposium. Program director Nassir Marrouche usually asks me to present something provocative.

My session assignment this year was a roundtable on the management of AF during the “blanking period” after ablation.

I took the opportunity to propose eliminating the blanking period.

I give credit for this idea to Drs. Mohammed Ruzieh and Andrew Foy. We recently wrote together in the American Heart Journal Open in favor of jettisoning the blanking period after AF ablation. We titled our piece Patients’ Lives Don’t Pause for the Blanking Period.

I also have a Medscape piece up on our argument as well.

My proposal at Western AF was not well-received. A few commenters agreed but most argued that we should still have a period of time after AF ablation where recurrences don’t count.

Let me tell you how the blanking period got established and then the reasons Ruzieh, Foy and I think it is wrong think.

Background

Much like cardiac surgery causes AF in the weeks post-op because of injury and inflammation, thermal lesions given in the left atrium during the ablation could also stir up arrhythmia. At least that is the theory.

My field came to the conclusion that some cases of AF in the weeks after ablation were not a failure of the procedure (due either to a wrong target or pulmonary vein reconnection from inadequate lesions) but rather inflammation that would subside with time. In fact, some early cases of AF never recur.

The challenge was that having AF in the blanking period greatly increased the probability of late recurrence of AF (procedural failure) but the correlation was not perfect.

The fact that some early AF resolve gave rise to the blanking period. Then it became ensconced. As if the sky is blue and we have blanking periods after ablation.

Blanking periods were also self-serving for ablation proponents. Because, In trials of ablation vs drugs, the ablation arm got a free ride for 90 days.

Reasons for Eliminating the Blanking Period

Reason 1: The blanking period falsely elevates our perceived success rate of AF ablation. A Vancouver-led group recently re-analyzed an ablation trial called Circa-Dose and found that shortening the blanking period from 12 to 8 weeks dropped the success rate of AF ablation by a statistically significant 5% (from 55% to 50%). Other papers have replicated this observation.

But you hardly need empirical studies, right? AF recurrences in the blanking period are common. Not counting episodes favors the ablation arm of studies.

Reason 2: No other areas of cardiology have such a blanking period.

At Western AF, I showed the example of the ISCHEMIA trial of delayed vs invasive strategies for patients who have positive stress tests. The main composite endpoint of the ISCHEMIA trial was not significantly different with either of the two strategies but controversy ensued over the rate of MI, which was one of the components of the composite primary endpoint.

For the primary endpoint, all MIs were counted, including those occurring immediately after the stent procedure. This comparison found no differences.

A secondary endpoint of non-procedural-related MI (see image) found that not counting MIs from the stent procedure resulted in the invasive arm having a 33% lower rate of MI. IOW, adding a blanking period in the ISCHEMIA trial led to fewer MIs. (But of course, patients cannot exclude an MI because it occurs after a procedure.)

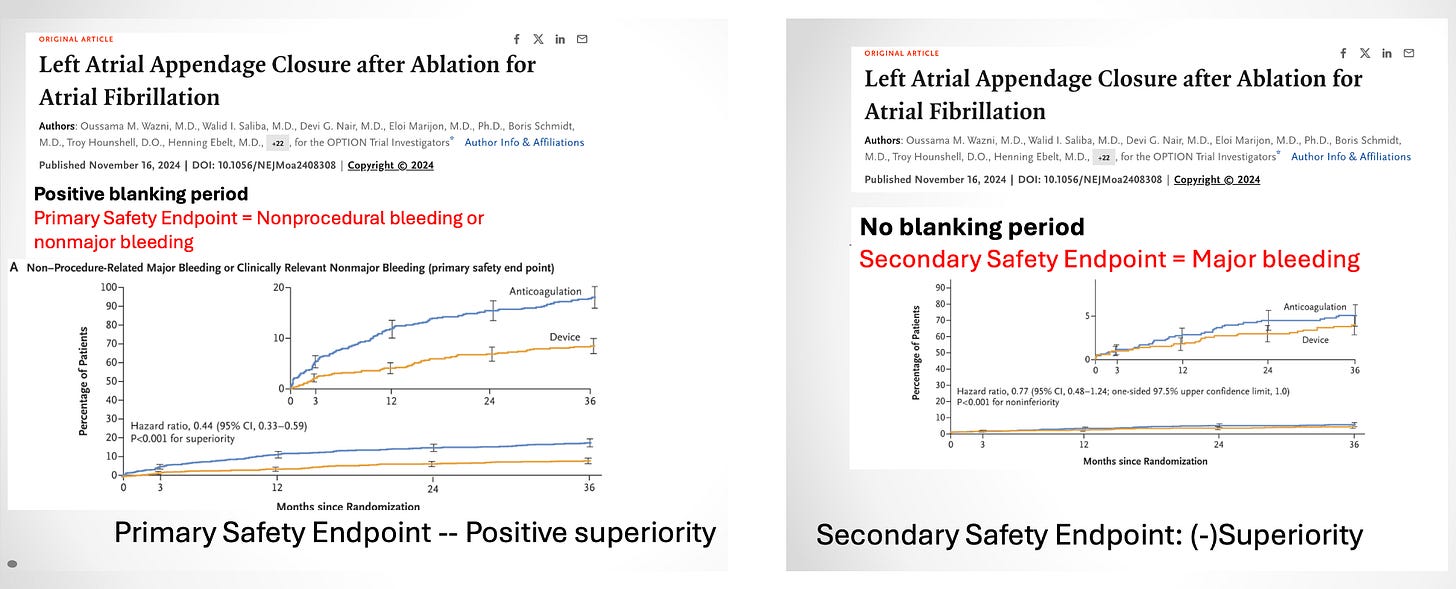

Another example of how a blanking period causes faulty interpretation of a trial came in the OPTION trial of left atrial appendage closure plus AF ablation vs oral anticoagulation after AF ablation.

Here, the primary safety endpoint (bleeding) was found to be superior in the left atrial appendage closure arm. But, the trialists designated the safety endpoint to exclude bleeding at the time of the procedure (e.g. a blanking period). A secondary endpoint of all bleeding found similar rates. IOW, without the blanking period, there was no advantage to the appendage closure device.

Reason 3: Ablation of AF has changed. Pulsed field ablation (PFA) uses electrical energy rather than thermal energy. PFA is also delivered through bigger multipole catheters. It’s faster, safer and likely leads to more durable ablation.

Why is that important? Because a recurrence of AF after PFA ablation more likely implicates a wrong target problem rather than a recurrence of conduction through the line of block that we attempt to create with point-to-point RF or cryoballoon ablation.

A recent study supports this notion. After reviewing more than 300 cases, investigators found that any AF that occurred more than 4 weeks after a PFA ablation was 100% predictive of more recurrences and a failed procedure.

Conclusions

It no longer makes sense to have a blanking period after AF ablation. A patient admitted to the hospital for AF one week after an ablation surely feels this negative outcome should count.

Of course, the caveat I offered the Western AF audience was that doctors have two mindsets. (We wear two hats if you will.)

One hat is our science or evidence hat. Here, we should surely count all AF episodes because it is the proper way to evaluate outcomes in studies. All AF counts for the patient and it should count in trials.

Doctors also must be clinicians and use judgement. Not having a blanking period does not mean that we need to take patients back for second ablations after an early recurrence. We can Stop and Think, and assess each patient and their specific situation. A blanking period should not obstruct clear thinking.

The blanking period violates two core principles: (1) intent-to-treat and (2) taking into account any patient experience that matters to the patient. Outcomes must be assessed immediately after treatment, but the severity of the outcome must be taken into account. If a procedure were to cause “minor” AF episodes, that should not count as much as a major spontaneous event. It is imperative to grade outcomes on an ordered scale.

The last 2 paragraphs sum it up for me. The research and clinical uses of “blanking period” should align, whereas currently they don’t.

The only reason to care about early AF recurrent episodes only detected on an ILR is if and when it ultimately predicts mid term clinical recurrence of AF, and hence clinical failiure of the procedure.

Based on Dr. Andrade’s recent study, it appears month 1 recurrences don’t really; month 3 recurrences often do; and month 2 might be a gray zone (for RF). So there is no reason to extend blanking periods beyond month 1 for RFA (for ILR asymptomatic episodes). By the same logic, since any recurrence at any time after PFA seems to predict mid term failure, there should be no blanking after PFA.

But symptomatic episodes matter, esp if symptoms are a component of the study endpoint. So there should be no blanking of any kind for any symptomatic AF event (and esp not for one that leads to a patient ER visit and cardioversion).